This is a paper I wrote last winter. With the omission of Howard Hassler (George B. McClellanShield of the Union) much of the popular opinion, through time, may be represented here.

---

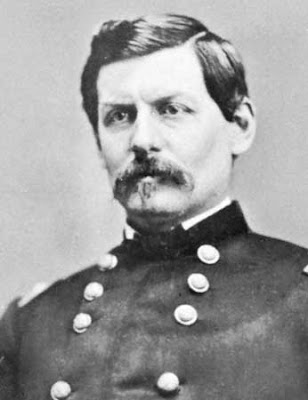

With predictable regularity, visitors to Antietam National Battlefield will encounter the photomural of Major General George B, McClellan and chuckle derisively, mutter a scornful remark, or assert to companions: “McClellan was an idiot.” Frequently someone will add “Yes, but he was a great organizer.”

Considering that these ideas may be both gross oversimplifications as well as factually incorrect, it is remarkable that they are so nearly universally embraced, and that those who express these opinions almost invariably use exactly the same words.

To examine the historiography of the Battle of Antietam is to find at the root of the popular understanding of the battle and its leaders General Francis W. Palfrey, eyewitness to the battle and an early critic of George B. McClellan. Palfrey’s intimate view of events as recorded in his pioneering history of the battle has influenced and continues to influence the work of both popular and academic historians in their interpretations of the battle and their opinions of the opposing generals.

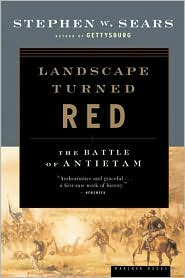

To examine Palfrey’s influence on the historiography of Antietam and McClellan this essay will focus upon one essential primary work, Palfrey’s 1882 history The Antietam and Fredericksburg as well as an influential grouping of subsequent historians, both academic and popular. In addition to Palfrey’s contribution other primary works cited include the recently published manuscript of Ezra Carman, author of the official history of the Battle of Antietam for the War Department. The tier of secondary works forming this inquiry includes: Bruce Catton, Stephen Sears, and Joseph Harsh. Supplemental support will be provided from the writings of James McPherson, James V. Murfin, Ethan Rafuse, and others. Within these works is a continuum of analysis spanning one hundred and twenty seven years, and over that time the reputation of George B. McClellan has suffered at an accelerating rate.

Francis Winthrop Palfrey, scion of a distinguished Cambridge Massachusetts family, served as Colonel of the 20 Mass Volunteer Infantry Regiment. Wounded at Antietam, he served for another year until his injuries forced him to resign his commission. He was promoted to Brigadier General in recognition of his distinguished and valorous service. As the founder of the Military Historical Society of Massachusetts, he was widely viewed as an authority on the battle of Antietam.

Palfrey’s The Antietam and Fredericksburg is a well-written and vastly informative micro-narrative of the Battle of Antietam. His recollections are clear and his analysis of the actions he was immediately involved in reflect his unique perspective and understanding of what was happening at the moment and informed by twenty years of reflection and research. His account of Sumner’s disastrous assault on the Confederates in the West Woods, resulting in the destruction of Sedgwick’s Division, of which Palfrey was a member, is as gripping an eyewitness account as one can hope to encounter. His writing style is intelligent and engaging, articulate and sometimes ironic. He is a very skillful writer who produced a very compelling interpretation of the battle.

However, as powerful as his descriptions of the combat are, one could question the ability of this former Lieutenant Colonel of an Infantry Regiment to fully appreciate the scope and magnitude of the greater events and meanings of what was transpiring around him as well as his judgments regarding the efficacy of the decisions made by those commanders in echelons far above his humble station. Perhaps it is his superior prose coupled with the unassailable credential of his role as a participant in the battle that causes his work to be cited by so many subsequent generations of historians.

Palfrey’s was the first published account of the battle, comprising one of the twelve volumes of the Charles Scribner’s and Sons Campaigns of the Civil War Series launched in 1880, a popular response to a generation of veterans reflecting upon and commemorating their part the nation’s watershed event. Palfrey’s work, though cited by nearly all scholars, is not particularly scholarly. Relying nearly exclusively upon his own memory, as well as the memory of other aging veterans, and advance copies of the then unpublished Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, Palfrey crafted a methodical portrait of the battle. Every inch the empiricist, Palfrey’s pages are awash with figures, troop strengths, projections of available reserves and re-enforcements, and numbers of casualties. Armed with numbers and two decades of hindsight, Palfrey attempted a scientific explanation of why, and how, Antietam should have been a crushing defeat for the Confederates.

Palfrey’s over-reliance upon the galleys of the Official Record is certainly understandable, as at the time the “OR” was exactly that, the “official record”. However, most modern scholars view the “OR” for what it is, a very helpful collection of primary sources that are very often ambiguous, inaccurate, or self-serving. For Palfrey however, the OR was a foundation for his scientific approach.

Palfrey, in his preface, makes this statement that should put critical readers on alert: “As I think that most readers are impatient, and with reason, of quotation-marks and foot-notes, I have been sparing of both.”1 Despite this lapse in scholarly procedure, no less an authority on Antietam than Stephen Sears will state in his new introduction to the 1996 Da Capo edition of Palfrey’s work “…even the closest students of the battle (including this one) will be seen nodding in agreement with most of his findings.”2 What is so unsurprising about that statement may be that although Palfrey’s history is critical of McClellan, though not overly so, Sears utilized it as a foundation work for the anti-McClellanism that has characterized much of his career.

Indeed, it is this vein of anti-McClellanism that characterizes the great bulk of the 20th century histories of the campaigns of the Army of the Potomac. No general of modern times, save for McClellan, at so young an age, rose so quickly, and achieved his objectives so completely only to be relieved of command and excoriated by historians for the remainder of time. It is Palfrey who sets this tone, though mildly and without seeming malice, that generations of subsequent historians have taken to greater, and less thoughtful, lengths.

That Palfrey brings no animus to the narrative is important to note. The vitriol will come from later historians. Indeed Palfrey sums up McClellan in very measured, nearly affectionate terms: “A growing familiarity with his history as a soldier increased the disposition to regard him with respect and gratitude, and to believe…that his failure to accomplish more was partly his misfortune and not altogether his fault.” 3 With that Palfrey ends his remarks on McClellan. One is given to wonder what Palfrey would make of the paucity of “respect and gratitude” that time has allotted to his former chieftain.

Palfrey, unfortunately for historic rigor, also set a pattern of judging McClellan by greater standards than he judged others. Palfrey was the first in a long line of historians who found fault with McClellan, the general who met all of his objectives, but praised Lee who failed in all of his objectives and nearly destroyed his army in the bargain. Palfrey also coined the McClellan postscript, which has become nearly obligatory: “His capacity and energy as an organizer are universally recognized.” 4 With that, a familiar mythology was established.

Palfrey’s methodical analysis of the battle had an impact far beyond his expectations. Beginning in 1894 Antietam Battlefield Board member, and participant in the Battle, Ezra A. Carman prepared an exhaustive research of the flow of the battle. Very much the empiricist, Carman would amass nearly 2,000 pieces of correspondence with veterans of the fight, responding to his four basic questions asking who was in the front, rear, left, and right, of each unit. Based upon this scientific approach Carman was charged with bringing some sense of order and empiricism to what is often described as the most confusing thirteen hours of the war. Carman’s mission was to establish rationalized boundaries for the proposed National Battlefield Park as well as to provide interpretive text for the 238 War Department tablets that remain on the battlefield to this day. According to Joseph Pierro, editor of the recently published The Maryland Campaign of September 1862: Ezra A. Carman’s Definitive Study of the Union and Confederate Armies at Antietam, Carman was greatly influenced by Palfrey’s pioneering history of the battle.5 Carman characterizes McClellan’s pursuit of Lee as “extremely cautious” 6 and uses the term “tardiness” frequently in that characterization.

Similar to Palfrey, Carman is critical of McClellan but stops well short of caricaturing the general or maligning him personally or professionally. Carman notes the lost opportunities inherent in McClellan’s generalship, but also reasonably, and charitably ascribes much of what were the general’s shortcomings to his relative youth and lack of military leadership experience. It should be remembered, as it was by Carman, that at the time of the Battle McClellan was only 35 years of age and his previous regular Army rank before being rocketed to the second highest ranking Major General in the Army, was merely a captain of cavalry. “It was fortunate for the Army of the Potomac and unfortunate for McClellan that he was its first commander. It was still more unfortunate for McClellan that he was called to high command too early in the war.”7 It is noteworthy that despite the empirical nature of Carman’s task he managed to insert so much in the way humanist reflection regarding the nature of McClellan.

U.S. Grant also alluded to the premature advancement of so young a general as McClellan as an unfortunate factor in his eventual fall from grace: “McClellan was a young man when this devolved upon him, and if he did not succeed, it was because the conditions of success were so trying. If McClellan had gone into the war as Sherman, Thomas, or Meade, had fought his way along and up, I have no reason to suppose that he would not have won as high a distinction as any of us.” 8

Carman closes one chapter with a reflection on what if Lee had won at Antietam, picturing a Confederate entry into Baltimore and Washington D.C. and concluded: “Antietam intervened to thrust aside that horror…it is very certain that to the present generation of men it can never appear otherwise than as a signal deliverance and a crowning victory.” 9 Carman, like Palfrey, tempered criticism with a qualified praise for McClellan as a soldier if not as a leader.

That tendency of tempered criticism would continue in the efforts of the venerable Margaret Leech Pulitzer in her 1941 Reveille in Washington, a micro-narrative that remains arguably the single best account of Washington D.C. during the Civil War. Leech’s narrative is a remarkably empathetic treatment of McClellan, beginning with his arrival in Washington “…a hero for a crowd which sorely needed one”10, to his sad though dignified farewell to his troops fifteen months later. Curiously, the 2004 book; Freedom Rising: Washington in the Civil War, Ernest B. Furguson’s somewhat redundant re-hash of the Leech classic, abandons the more moderate approach of Leech and with descriptors like “dithering” 11 continues, what by 2004, is the norm for McClellan treatments, a scornful rather than objective tone.

The historiography of the Battle of Antietam and the generals involved increased exponentially with the approach of the centennial of the Civil War. The “centennialist era” would produce prodigious histories and historians with familiar names, possibly none more so than Bruce Catton, newspaper editor turned popular narrative historian. Catton’s engaging writing style, interest in the Civil War, and business acumen coupled with his appreciation of “a good yarn” produced numerous volumes of best-selling popular histories of the American Civil War. Catton, like Palfrey, is both measured and thoughtful in his criticisms of McClellan, though there is a progression. In his 1951 Mr. Lincoln’s Army, Catton opines of McClellan’s Antietam generalship: “Masterpiece of art it assuredly was not: rather, a dreary succession of missed opportunities. “ 12 By 1963 Catton, in his more scholarly Terrible Swift Sword took a more nuanced stance on the general’s abilities: “…if he had been just a little more aggressive he would have saved Harper’s Ferry, mashed the fragments of Lee’s army, and won the war before September died.” 13

Concurrent with the appearance of Terrible Swift Sword Historian James V. Murfin produced his landmark Antietam work The Gleam of Bayonets. The influence of Murfin’s scholarship cannot be overstated. His is a long shadow; even the auditorium of the visitor’s center at Antietam National Battlefield is dedicated to Murfin. Murfin, in his somewhat psychological narrative brought a new level of scorn for McClellan, citing “blunder” and “cover-up”.14 Murfin charges McClellan with self-destructive negligence in his generalship, referring finally to Antietam, the battle that changed the nature of the war to one of liberation, as simply “McClellan’s Folly”.15 With Murfin, the moderate tone set by Palfrey and followed by others had come to an abrupt end.

Through the haze of vitriol, lapses in Murfin’s scholarship begin to stand out including this patently incorrect assertion: “Antietam would go down in history as a stalemate, a draw between two armies…”.16 To make this statement is to deny McClellan’s successfully achieving his only two military objectives, those of defending Washington while simultaneously driving the Confederates out of Maryland. What Murfin began Stephen Sears continued, with the inevitable Palfrey in the bibliography of both.

Landscape Turned Red, Stephen Sears’ 1983 contribution to the continuing historiography of the event is both a compelling battlefield narrative as well as a cementing of the anti-McClellan movement established by Murfin. Sears escalates the invective against McClellan with pseudo-psychological characterizations such as: “His arrogant contempt for the administration, his delusions about his enemy and his God-given mission, his incessant search for scapegoats was in daily evidence”. 17 Sears’ ramping up of this contempt for McClellan begins to interfere with his scholarship as evidenced in this passage regarding the outcome of the Battle of Antietam: “…the Army of Northern Virginia could justly claim a victory”. 18 This ludicrous conclusion would be more at home in a Confederate heritage newsletter rather than a serious academic study.

Sears makes generalizations regarding McClellan’s motivations and character that reveal Sears’ Freudian leanings: “Conceivably on another field on another day he might overcome his crippling caution and his distorting self-deceptions and his lack of moral courage in the heat of battle”. 19 One can only wonder what Palfrey and Carman would have made of such vituperous assertions.

Telling is the index of Sears’ 1988 biography of McClellan in which the reader will find these successive entries under “McClellan”: “…self deception, appearance of competence, aggrandizement, messianic complex, fatalism, arrogance, inflexibility of thought, obstinacy…”. 20 Predictably, in finding faint praise for McClellan, Sears relies on the tried and true; “His notable achievement in organizing and training the army would be his monument.” 21

The intensity of Sears’ criticism gives this reader pause. Unlike Palfrey (seriously wounded at Antietam) and Carman who had a personal stake in the story, Sears made his observations from a position removed from the threat of battle, yet wrote with a passion that betrays what seems a very non-scholarly anger with the long-dead McClellan.

The consequences of Sears’ assessment of McClellan are made manifest in this New York Times book review of October 30, 1988: “Stephen W. Sears already has given us ''Landscape Turned Red,'' the best account of the Battle of Antietam, one of McClellan's conspicuous failures. Now Mr. Sears provides a detailed, scrupulously fair account of the general's entire career - particularly his unparalleled war opportunities and his persistent efforts to blame others for his inability to master them.”22 As Sears convinces the New York Times so does the New York Times convince its readership, all the while, Palfrey’s hoped for “respect and gratitude” for McClellan becomes the dimmest of memories.

It is interesting to note that amidst this tumult, academic-cum-popular historian James M. McPherson reverted to a non-provocative centrist position in his 2003 best-selling Battle Cry of Freedom. As the discussions of others progressed toward the demonization of McClellan, McPherson returned to the decade earlier Catton-esque tone of moderation, perhaps in reaction to the distasteful clamor or perhaps for more comfortable commercial reasons. Nonetheless, McPherson brought little new thinking to the issue as evidenced in this insight; “Ever cautious, however McClellan made careful plans…” 23 and is noted here simply as a sequential anomaly in the historiographic continuum.

“Fear of failure”24 is the bit of psychoanalysis brought to the discussion by historian Joseph T. Glatthaar in his 1994 Partners in Command: The Relationships Between Leaders in the Civil War. Glatthaar echoed much of the tone and prose of Sears, referring to McClellan’s self depiction “as a Christ-like figure”, “Like Jesus Christ before him, McClellan refused to alter or avoid his fate.”25 With assertions such as these the historiography veered dangerously close to caricature. The open season on McClellan declared by Murfin was being exploited to a high degree by those who came after him including Sears and Glatthaar as well as historians of less monumental stature.

Just as one might begin to fearfully wonder to what extremes this progression of interpretation would descend, an abrupt and recent course correction occurred. Two new voices, with new interpretations arrived upon the scene, and the historiography of the battle and the Federal commander have, hopefully, swerved back toward a more measured, reasonable, course.

In 1998 historian Joseph L. Harsh launched a monumental trilogy of histories exploring the 1862 Maryland Campaign from the point of view of Confederate commander Robert E. Lee. In the second volume, Taken at the Flood: Robert E. Lee and Confederate Strategy in the Maryland Campaign of 1862, Harsh opens on a note of caution: “It would be frivolous, even counterproductive, to reduce such a richly instructive story to a Grimm’s fairy tale replete with fair heroes and foul villains. It is not necessary to oversimplify history to make it entertaining. The historian needs to admit frankly that no event, or any of its parts, can ever be known with a certainty…”.26 Harsh cautions that the role of history is understanding rather than escape and that history, as life, is full of ambiguity, “Ambiguity is long, life is short”. 27 This is certainly a psychological study as Harsh strives to take the reader through all of Lee’s motivations and fears as he prepares for battle with McClellan. Although Lee is the focus of Harsh’s study he does, specifically, take Murfin and Sears to task for holding McClellan to a different standard of judgment than they did Lee. 28

The scholarship of Harsh is reflected in his bibliography with a staggering 461 cited entries, contrasted with the 176 entries in the bibliography of Landscape Turned Red. Harsh utilized a broad array of primary and secondary sources nearly all of which were available to, though unused by Sears, and as a result comes to some very different conclusions than Sears. Whether or not this is reflective of better or worse scholarship on the part of either becomes apparent upon reading Harsh’s superior work.

Though advancing age may prevent Harsh from continuing this remediation of George B. McClellan, his message and influence are apparent in the writings of professional historian Ethan S. Rafuse.

Rafuse provides a provocative rehabilitative effort in his 2005 master narrative McClellan’s War: the Failure of Moderation in the Struggle for the Union, a study that places the war and McClellan in the broader intellectual context of Whig philosophy and a changing America. Rafuse is the first to look at McClellan from the Whig perspective of moderation and a limited war. After much convincing argument Rafuse concludes: “it is not unreasonable to find more to praise than condemn in McClellan’s performance during the 1862 Maryland Campaign.” 29 With that, the historiography, though now psychological rather than empirical, returns to Palfrey’s moderation, indeed, Rafuse went beyond Palfrey to actually praise the generalship of the Commander of the Army of the Potomac.

An interesting postscript to this 127-year long journey can be found even earlier than Palfrey’s pioneering work. Robert E. Lee, in 1870, was asked by his cousin, Cassius Lee, which Union General he thought the greatest. “McClellan, by all odds!” 30 was the old warrior’s unhesitating answer.

Returning to the perceptions and prejudices of those visitors at Antietam National Battlefield; to imagine that they can or will overcome the burden of so much folklore, mythology, and oversimplification and appraise McClellan with new eyes, may be too much to expect. We grow comfortable with our folklore despite the evidence that proves it false. It may be the pithy quips of Abraham Lincoln and vitriol of Stephen Sears that has formed the enduring popular image of General McClellan.

The historiography of George B. McClellan and his role at Antietam has evolved over time and today is somewhat closer to where it began, with the measured criticism of General Francis W. Palfrey. That it took such a wild ride? To paraphrase Palfrey, “The fault was in the historians.”31

Notes

1. Francis W. Palfrey, The Antietam and Fredericksburg (New York: Da Capo Press, 1996), Preface.

2. Palfrey, The Antietam and Fredericksburg, ix.

3. Palfrey, The Antietam and Fredericksburg, 135.

4. Palfrey, The Antietam and Fredericksburg, 134.

5. Joseph Pierro, e-mail message to author, 27 March 2009.

6. Joseph Pierro, The Maryland Campaign of September 1862: Ezra A. Carman’s Definitive Study of the Union and Confederate Armies at Antietam (New York: Routledge, 2008), 87.

7. Pierro, The Maryland Campaign of September 1862, 394.

8. John Russell Young, Around the World with General Grant: A Narrative of the Visit of General U.S. Grant, Ex-President of the United States, to Various Countries in Europe, Asia, and Africa, in 1877, 1878, 1879; To Which Are Added Certain Conversations with General Grant on Questions Connected with American Politics and History, vol 2 (New York: American New Company, 1879) 216-17.

9. Pierro, The Maryland Campaign of September 1862, 379.

10. Margaret Leech, Reveille in Washington: 1861-1865 (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1941), 108.

11. Ernest B. Furgurson, Freedom Rising: Washington in the Civil War (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004), 11.

12. Bruce Catton, The Army of the Potomac: Mr. Lincoln’s Army (New York: Doubleday and Company, Inc., 1951), 321.

13. Bruce Catton, Terrible Swift Sword (New York: Doubleday and Company, Inc., 1963), 450.

14. James V. Murfin, The Gleam of Bayonets: The Battle of Antietam and Robert E. Lee’s Maryland Campaign (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1965), 270.

15. Murfin, The Gleam of Bayonets, 327.

16. Murfin, The Gleam of Bayonets, 289.

17. Stephen W. Sears, Landscape Turned Red: the Battle of Antietam (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1983), 32.

18. Sears, Landscape Turned Red, 309.

19. Sears, Landscape Turned Red, 338.

20. Stephen W. Sears, George B. McClellan: the Young Napoleon (New York: Da Capo press, 1988), 474.

21. Sears, Landscape Turned Red, 338.

22. Tom Wicker, book review, 30 October 1988, In The New York Times Books, http://www.nytimes.com/1988/10/30/books/a-case-of-the-slows.html, accessed 31 March 2008.

23. James M. McPherson, The Illustrated Battle Cry of Freedom (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 461.

24. Joseph T. Glatthaar, Partners In Command: The Relationships Between Leaders in the Civil War (New York: The Free Press, 1994), 85.

25. Glatthaar, Partners In Command, 91.

26. Joseph L. Harsh, Taken at the Flood: Robert E. Lee and Confederate Strategy in the Maryland Campaign of 1862 (Kent, Ohio: The Kent State University Press, 1999), 9.

27. Ibid.

28. Harsh, Taken at the Flood, 487.

29. Ethan Rafuse, McClellan’s War (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005), 331.

30. Captain Robert E. Lee, Recollections and Letters of Robert E. Lee (Old Saybrook, CT: Konecky & Konecky, 1998), 416.

31. Palfrey, The Antietam and Fredericksburg, 127.

Works cited

Catton, Bruce. The Army of the Potomac: Mr. Lincoln’s Army. New York: Doubleday and Company, Inc., 1951.

Catton, Bruce. Terrible Swift Sword. New York: Doubleday and Company, Inc., 1963

Furgurson, Ernest B. Freedom Rising: Washington in the Civil War. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004.

Glatthaar, Joseph T. Partners In Command: The Relationships Between Leaders in the Civil War. New York: The Free Press, 1994.

Harsh, Joseph L. Taken at the Flood: Robert E. Lee and Confederate Strategy in the Maryland Campaign of 1862. Kent, Ohio: The Kent State University Press, 1999.

Lee, Robert E. Recollections and Letters of Robert E. Lee. Old Saybrook, CT: Konecky & Konecky, 1998.

Leech, Margaret. Reveille in Washington: 1861-1865. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1941.

McPherson, James M. The Illustrated Battle Cry of Freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Murfin, James V. The Gleam of Bayonets: The Battle of Antietam and Robert E. Lee’s Maryland Campaign. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2004.

Palfrey, Francis W. The Antietam and Fredericksburg. New York: Da Capo Press, 1996.

Pierro, Joseph. The Maryland Campaign of September 1862: Ezra A. Carman’s Definitive Study of the Union and Confederate Armies at Antietam. New York: Routledge, 2008.

Rafuse, Ethan. McClellan’s War. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005.

Sears, Stephen W. George B. McClellan: the Young Napoleon. New York: Da Capo press, 1988.

Sears, Stephen W. Landscape Turned Red: the Battle of Antietam. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1983.

Wicker, Tom. Book review, 30 October 1988, in The New York Times Books. http://www.nytimes.com/1988/10/30/books/a-case-of-the-slows.html. Accessed 31 March 2009.

Young, John Russell. Around the World with General Grant: A Narrative of the Visit of General U.S. Grant, Ex-President of the United States, to Various Countries in Europe, Asia, and Africa, in 1877, 1878, 1879; To Which Are Added Certain Conversations with General Grant on Questions Connected with American Politics and History, vol 2. New York: American New Company, 1879.

13 comments:

Very nice, Mannie.

Wow, simply outstanding. Very informative!

I had the pleasure of visiting Antietam Battlefield for the first time this past November. It was a moving experience. The visitor center is also well done.

I just stumbled upon your blog and will add it to my blogroll.

Thanks,

Geoff Elliott

The Abraham Lincoln Blog

Dear Sir,

Thank you for sharing this well-written post."Little Mac," was not a diplomat but he was a professional.

cordially,

David Corbett

Mannie,

I hope you are going to do a similar paper on Burnside at Antietam??? Thanks for an excellent recap of McClellan's "ups and downs" in the eyes of historians.

Ron Dickey.

Now Mannie how am I going to respond to the question, "What's up with McClellan?", if you give away all the answers?

John C. Nicholas

An excellent summary of the scholarship. It seems to be your contention that the characterization of McClellan which prevails today began with Palfrey's book. While it's understandable that you focus on Antietam given your association with the battlefield, to use a phrase popular with historians the battle "did not occur in a vaccum." Little Mac was certainly bringing some baggage to Sharpsburg. I wonder what you think of his disappointing performance on the Peninsula, including his failure to be present on practically any battlefield on which his men were fighting.

I have no wish to attack the scholarship of any of the historians you cite, but sometimes it seems that rehabilitation of a damaged reputation can swing too far the other way.

Mannie,

If you haven't already read them, here's two more to check out:

General George Brionton McClellan: A Study in Personality, by William Starr Myers (1934) - very pro Mac;

George B. McClellan & Civil War History, by Thomas J. Rowland, 1998 (this book gets denigrated by many Grant & Sherman fanboys as "tearing down others to build Mac up", but seems to be a pretty good attempt at viewing them all through an objective lens).

Excellent summation Mannie.

T. Harry Williams was also not a McClellan supporter as shown in his book "Lincoln and His Generals."

For me, had not McClellan been so candid in his letters to his wife, I might think better of him. Modern historians who make efforts to rehabilitate Little Mac IMO have a tough row to hoe given these letters as well as some of his telegrams and statements.

Larry F.

Great analysis Mannie and much food for thought for those of us interested in McClellan

Great Essay Mannie!,

I have most of the books you mention and enjoyed your critique of them and their depiction of McClellan. McClellan reminds me a bit of Douglas MacArthur. There are (and were) strong opinions of him and you seemed to either love him or hate him and there is no in between. Both of their egos were also quite immense.

Thanks,

Chris

I have been meaning to respond for about a week now. I think the main reason McClellan has been trashed is to maintain the myth of the all-knowing, all-wise Abraham Lincoln. If McClellan was a good general, then one might conclude that Lincoln made mistakes in his dismissals of him. I don't know enough to write authoritatively, but two pro-McClellan items have stuck in my mind. One is the continuing loyalty that Henry Livermore Abbott, one of Palfrey's junior officers in the 20th Mass., had for McClellan, and his letters implied that his sentiments were shared widely. The other is a letter from the regimental surgeon of the 20th, Nathan Hayward, to his father, upon Grant's reaching Petersburg in June 1864. He wrote, "I suppose the country is at last satisfied that McClellan's projected approach by the south side of the James [River] was good generalship after all." (R. Miller, Harvard's Civil War, p. 386) The letter implies that McClellan was planning to move to the south of the James, toward Petersburg, in the summer of 1862, which would have put him where Grant finally arrived in June 1864. To think that if Lincoln had not cashiered McClellan, the armies might have moved into siege operations in Petersburg in 1862, possibly avoiding Antietam, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, and the Overland Campaign. It boggles the mind.

Bvt Brig. Gen. Frederic Winthrop was another blueblood who admired McClellan and had little use for Lincoln, sometimes referring to him as "Uncle Abraham" in a sarcastic way. I highly doubt that Ken Burns would have given him voiceover time if he'd read his letters.

And now we can add to the pile with Edward H. Bonekemper III's Mcclellan and Failure: A Study of Civil War Fear, Incompetence and Worse.

A study? Really?

Guess anybody can get anything published these days.

Cheers,

Jimmy

Post a Comment